|

24 Hours in Kolno

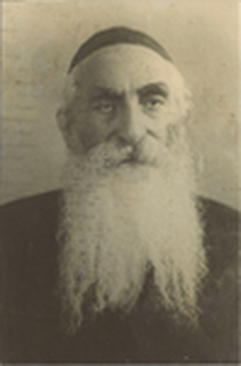

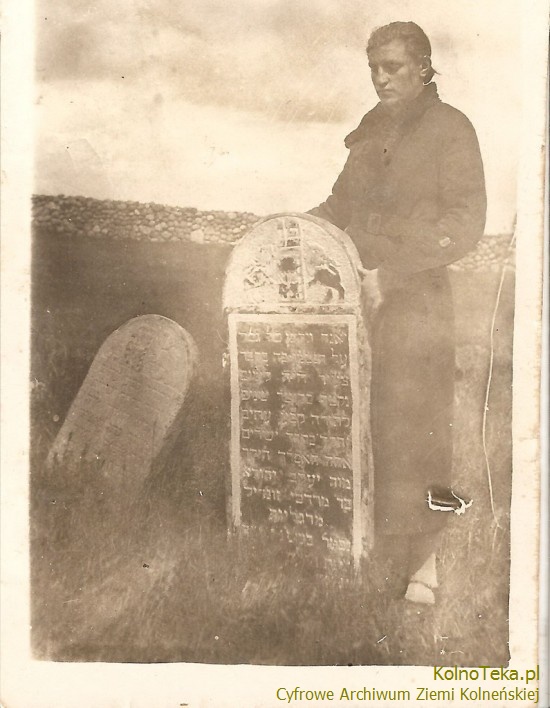

July 31-August 1, 2012 It was with heavy trepidation that I accepted my friend Darius’ invitation to teach and perform healing ceremonies in Poland following my trip to Istanbul. I had a lot of ambivalence feelings. My parents had never wanted to go back to visit it, never wanted to speak that language again or teach it to us, and I found listening to it as repulsive as German. My parents shared very little with us from their past. From their point of view, they closed the book on Poland. But I always felt unexplained pull, curiosity and mysterious connection to that far away and forbidden place. From time to time in my childhood I would pull out their old decorated wood-covered photo album and looked at the black and white photos. “Who are those strange looking people?” I asked my mother trying to read the faded hand written inscription on their back . Many times, late at night, I have logged on to Google maps to find Kolno and Brestowiche, my parents’ towns and imagined how they look. My cousins, Tami and Aviva, had made a daring trip to Kolno in April 2012 where they met Wlodek, who upon hearing that the “Israeli delegation” is visiting the Jewish cemetery of Kolno, took his wife on her wheelchair and ran to meet them there. It was almost enough to satisfy my curiosity. Almost enough. I wanted to see it in my own eyes. Here I was flying from Istanbul toward my mother’s birthplace. Sitting by the window I could view Poland from above. As we crossed the southern mountains and came close to Warsaw, I could easily see the dark green forests, the heavy soil, the crawling rivers, the many small farm houses and villages dotting the flat landscape. Maybe leaving hot, sunny Istanbul and arriving to a cloudy sunset in Warsaw had an affect on my mood. Looking down, my thoughts took me to the stories I heard about the War, of Jews who escaped and lived in those forests, crossed those bridges, and hid from the Nazis and their Polish cooperators in those farms. And now we landed. A strange homecoming, I thought. The sweet citrus smell of my Aqua Florida, the cologne I use in my healing ceremonies, had already overtaken the conveyor belt when I finally discovered my missing baggage. It had been thrown inside the baggage loop. I picked it up and recovered the broken bottle. I rushed to meet the two men who I knew were waiting for me at the arrivals gate of the modern Warsaw airport. Darius wore his signature white fedora, a white shirt, a colorful beaded necklace and wrist bands from the jungles of Colombia. He gave me a big happy smile as I emerged. next to him was Wlodek, a man in his early sixties with a high forehead, light hair, and piercing blue gray eyes smiled widely and shook my hand. I was surprised. The resemblance to my older brother Yossi could not escape me. We exchanged laughs and hugs and went outside to Wlodek’s Peugeot camper in the parking lot. Darius and I sat on benches facing one another exchanging stories, nibbling on the waiting welcoming cookies and drinks set by Wlodek. Wlodek took the driver’s seat, turned back to make sure we are eating, and off we went to Warsaw. It was then that Darius let me know he would not join us. “I need to manage your workshop registration. And besides, Wlodek wanted to surprise you with stops in a few places before you reach Kolno, your final destination,” Darius said with a typical mischievous smile. “Ok, why not, it might be fun,” I replied, laughing naively. I did not know what to expect and what is coming. The Aqua Florida gave the camper a familiar Ecuadorian healing smell as we went on our way to Warsaw. A few minutes into our trip, we stopped to see the famous square commemorating the Russian Liberation Army’s liberation of Poland. With a sly smile, Wlodek showed me the huge square with impressive socialist-style monumental sculptures of soldiers. Well, I thought, the first of my surprises. Wlodek served us coffee and offered more food in the camper before we went on to drop Darius off at the main train station, an impressive modern structure reminiscent of an airport terminal. “Here,” said my tour guide, “was the border of Ghetto Warsaw. All this area of 400 hectares was the ghetto. You can’t see it because nothing is left.” My stomach churned. In my mind I could see young Mordechai Anielewicz and his fellow Hashomer Hatzair members, the ghetto walls, the old and young people in those black and white pictures; it all came to life in my mind. But nothing was left. We continued northeast, out of the city. I could not have been more impressed by the modern and experimental architecture of the new Warsaw. About 95 percent of this city was flattened out at the end of the War, and has now been resurrected as a combination of reconstructed old and new buildings. We were passing some old war-era buildings that reminded me of the books and documentary films I had seen as a boy. At a traffic light, Wlodek turned his face to me and announced the second surprise. “We will spend the night in the camper in the parking lot of Treblinka,” he said matter of factly--it wasn’t an option. I stop breathing. I am sure he saw the horror in my eyes and, as my face turned white, I said: “Sure. Why not...” I had intentionally planned this trip to avoid going to any concentration camps and certainly not this famous Nazi death camp. My father-in-law, Chaim Rubin, had bravely escaped it and now I would voluntarily spend the night. Yes, a surprise indeed. I was quiet for a long time. Wlodek kept driving and pointing to different important buildings and places, but I could not focus. As the darkness thickened my thoughts traveled to the forests along the roads and the rivers we were crossing. Is that where Chaim hid after escaping with a group of teenagers from Treblinka? Is this what he breathed and smelled? Are those the same crows calling him? Shivers spread through my body in waves. We kept talking about Kolno, my mother’s ancestral village, which we headed towards. All of the sudden Wlodek began singing a Yiddish song. I froze. It was the same song Chaya Borenstein, my wife Margalit’s mother, who escaped as a young and thin twelve year old through a small window in the train to Auschwitz, sang to us with so much passion. It was a song of her vanished family. She used to force our kids to learn every word. “Oy, oy, oy Beltz, mayn shtetele Beltz, Mayn heymele, vu ikh hob Mayne kindershe yorn farbrakht. , .......”. Immediately my survival mind interjected. “Who gave Wlodek permission to sing it? Is he Jewish? Is that a secret code to let me know? Does he want to impress me? Should I join him?” But I could not. I refused. We went on driving on an endless straight road designed by King Nicholas. As the story goes, he did not like curved roads and ordered his engineers to make them straight. A big green road sign with the name “Bialystok” appeared in bright white. “Bialystok? I heard of it all my life, my father used to go there for Hashomer Hatzair meetings. Is it here? The white city?” I asked Wlodek. Krakow, Lodz, Lublin, Vilna--all those mythological names we grew up hearing about are here. On traffic signs, they are real for the first time. “Here in a few kilometers we need to turn right. I hope I remember where it is,” Wlodek said. As we turned, Wlodek announced that in order to sleep better we need to buy two big Polish beer bottles. “Do you like dark beer?” He asked. “Sure.” I happily agreed. A few miles later we stopped in a tiny village by a food store, the only place that was open so late. A group of young men with shaved blond hair were smoking and drinking beer, laughing under the streetlight. We parked our caravan by the store and they all looked at us as if we had just come from the moon. “Don’t say anything to them,” Wlodek sternly warned me. We climbed down, the kids moved backward and started to ask us teasing questions. I could feel the tension building. This could be like the gangs of Polish men who passed the Jews to the Germans, I thought. I turned to them. “Good evening, how are you?” I said in English. They were shocked and moved away. We got the beer and fled. “Fifteen more kilometers and we will be there,” Wlodek announced. My heart sank deeper. I was not looking forward to it. Soon we turned right again and started to drive on a cement road. “This is the original road,” Wlodek said somberly. “It was built by the Jews.” “Sokolow - 31 Kilometer,” a road sign appeared in front of us. “I know this name,” I told Wlodek, trying to remember. “Yes, that is the name of Chaim Rubin’s town.” It was so close, only half an hour away from here. “Do you want to go there now?” Wlodek asked. “No. maybe next time,” I answered. We moved on in silence. The camper rattled on the cement road. Then we stopped. “You see this,” he pointed in front of us, “these are the original train tracks they used to transport the Jews.” Wlodek continued driving. Soon the road sign of Treblinka appeared in the dark on our right. And finally we rolled into the parking lot. It was half past midnight. We were there, all by ourselves. The full moon hung above us in the clear starry, chilly night. “Were the prisoners here able to enjoy this scenery too?” I asked myself. Wlodek seemed distressed. “I don’t sleep much these days, especially after I lost my wife, my best friend, a week ago, and I don’t have my sleeping pills,” he said with tears in his eyes. He took out the two large beer bottles, handed me one and we both gobble them up. “We have to sleep now, the sun rises at 4:30, we are in the north you know.” He ordered me. I climbed out of the caravan and went into the forest between the trees and placed my hand on a big old tree. Earlier, Wlodek had told me: “The German destroyed all the evidence. Only the old trees remember what really happened here. If you want to know the truth, touch them.” I did not expect such a deeply perceptive shamanic observation. Here, in this place, Chaim escaped with a group of youngsters. Maybe he touched this tree, those leaves. Was he scared? The ground was so wet. Did he have something warm to wear? Did he have shoes? How could he survive this wetness and cold? And it is not even winter. He was only a boy of 15 or 16 with a few sisters. Was he worried about his parents that he left behind in the camp? Did he know what would happen to them? These thoughts rushed through my mind. Tova, his wife, told us of his recurring nightmares: “He used to jerk up in his sleep in the middle of the night, covered with cold sweat, shaking and yelling in Yiddish with wide open eyes: ‘Run away, run away, the Germans are coming...’ Shush...I told him nobody is going to hurt you. I calmed him down, I hugged him and he fell asleep again.” The horrible silence in these woods grew louder in my head. “Come in, Itzhak,” I heard Wlodek calling me. I climbed up, happy to smell the familiar healing Aqua Florida. The bed was already set for me above the cabin and I crawled in. Wlodek made his bed on one of the benches. “Good night, Wlodek. Thank you for bringing me here.” I said and closed my eyes. But I could not sleep. All I could see were millions of tiny sparkling lights. “The souls of the dead are alive”, I thought. I was praying hard for them. It was a few minutes later that Wlodek woke me up. “Let’s go, it is already 4:30, the sun is up, let’s eat something.” Wlodek prepared tea in his kitchen and put something to eat on the table. By 5am we started our walk into the death camp. It was just the two of us: a Polish man whose farming family lived just 500 meters from my Jewish family’s home and store in a small border town called Kolno. I am sure my mother, who was born in 1910 on a Saturday between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, knew his mother. Maybe she even shopped in our store. Both of us were born on the same year, in a space of a few months. Surrounded by 800,000 living souls, both of us were trying to understand and come to terms with what happened here in those dark years of madness. Words are inadequate to describe all the contrasting emotions I felt walking on the stone road, built by Jewish prisoners, towards Treblinka. Touching the metal train rails, I stood on the deck where the Jews were unloaded, stripped, and sent to the crematoria just a such short distance away. I walked in a daze and put my hands on the black melted floor of one of the gas chambers, all that was left. I made a long prayer for those souls, maybe even the parents and sisters of Chaim, in his name. How could they do it, the Germans, the Polish? How can human beings be so evil, shut their hearts, twist their minds and find the cruelty to plan and execute such heartless and senseless acts in such industrious ways? It is beyond any words or understanding. We walked around the huge stone memorial monument. I lit a candle and walked aimlessly, between the thousands of stones bearing the names of all the towns, villages and shtetels from which Jews were taken to be eliminated. The sun rose higher. “Until now I can’t understand why they did not destroy the only bridge that leads to Treblinka,” Wlodek said, shaking his head. “Who?” I asked. “The Polish resistance movement, the Russians, the West. All it would take is one bomb from the air or a few explosives, and so many lives could have been saved.” We were silent. “We have to go, Itzhak,” Wlodek said quietly. I want to take you to visit two other mass graves closer to Kolno, and it is still a long way. Let’s go.” In the silence I could hear the crows, the chirping birds, and I could hear the distant sound of cars rattling on the cement road, sounding more like oncoming trains. I bent down and dug out two small stones from the road the prisoners built and put them in my pocket. We boarded our camper. I was thankful that the Aqua Florida brought me back to reality again. We left in silence, before the daily tourist busses arrived. Back on the straight road, I could see now in the soft daylight the beautiful pastoral Polish farms, cows, rivers and forests. My thoughts drifted and I wondered: is this is the farm where Chaia hid, after running alone from the train, bullets shrieking all around her, leaving all her family behind? Is this is the goose barn where she was raped by her Polish farmer “savior”? Is this is the wooden farmhouse Chaim found her in and convinced her that she is really Jewish and she should go with him to Israel? How can they, and others who went through thishell, be “normal?” Wlodek stopped by a gas station and made us breakfast. We talked and shared stories and feelings from our morning in Treblinka. Wlodek told me of how the Germans bombarded the Poles on the first day of the invasion with artillery, and shot innocent people to frighten the population so they will cooperate with them. He told me how the German soldiers shot the Poles who were found hiding Jews in their homes, in public. Young Poles were forced from their homes to dig up bunkers, and were shot if they resisted. I could sympathize with them, too. There were no winners here. I admired Wlodek’s integrity, generosity and humanity. His big open and loving heart gave me comfort, dealing with all those emotions. I was so happy to share this experience with him, true family and a friend. “Here we have to turn left,” he said. Msciwuje, the road sign said. The dirt road led us to agricultural fields connecting the next village over. “I think it is here, on the left,” he said, unsure. “Look, do you see the Russian bunker on this hill? This was the border, there are so many here.” He stopped the camper on the edge of a corn field. “Behind this border, really not so far, is Brestowice, my father Chaim Koledjanski’s family village, in today’s Belarus,” I told him. I wonder where his family and parents were taken and buried. We stepped out. It was gray, cloudy, and soft rain drizzled now. We started walking toward a lone tree in the middle of that tall corn field and used both our hands to swim forward through the stalks to make a path. Suddenly, we were there, surrounded by white marker stones connected by a metal chain. In the center of that long rectangle, a reddish memorial stone stood silently to mark this grassy mass grave. Small memorial stones were tucked into its base and above it. There was no mention of the 4,500 women and children from the area, including Kolno, who had to dig their own grave, that were shot and buried here. There was no mention on that stone that they were Jews, and possibly my mother’s family. Wlodek said he had heard from a farmer friend that their screams and cries were so loud that farmers four kilometers away heard them until the machine guns silenced them forever. But no one then and no one today is willing to talk about it, as if it never happened. “Wlodek, why is it that there is no access road to it?” I asked him as another car passed us by; the couple inside just turned their faces away. I could hear their desperate cries even now and I suspected that Wlodek could hear them too. “Come, I want to show you another mass grave where they shot and buried the men, and then we will go to the Jewish cemetery of Kolno. It’s getting late,” Woldek said. We visited the next one, at Kolimagi. Wlodek was upset that the government marked just a small area, and did not mentioned that the men were Jews. He walked around showing me evidence that the grave was much larger in size. He said he once found human bones far away from where the memorial was built. We arrived at the Jewish cemetery at noon, and the sun was high and hot. The gate was wide open. “When Tamar and Aviva, your cousins, were here in April, they had to get the key from the keeper in that house,” and he pointed to the direction of a house not too far. You see the wall? It was built three times since the War.” Wlodek said. We entered into a green sea of tall wild flowers and plants which covered the entire large area. I could see some headstones but most were buried within the grass or under the ground. “I will find my grandfather’s stone!” I said to Wlodek. “Well, according to the picture of your aunt Leah, it should have been here.” And he pointed to a place a few meters from the wall. I started vigorously clearing the stones, pulling out the plants. After a while even I understood it is not a job for one person. “You may never find it since some headstones were stolen and resold to regular Poles, then engraved with new names on the backs.” On our way, finally, to Kolno we continued to discuss ways to clear and preserve the cemetery. Maybe we can raise money from relatives in Israel or the States and contribute it to a school that will agree to clear it and learn about who these people were, I suggested. “Maybe we can bring a group of young Israelis here to do it with a group of local Polish kids, so they can meet and know each other?” Wlodek suggested. “Great idea”, I agreed. We left the Jewish cemetery and headed to our last stop, the visit to the mythological, bigger than life, Kolno, where my mother’s family story had begun. We took a short rest and had some food at his beautiful and comfortable two-story house on the corner. Michal, Wlodek’s son, a sweet father of two energetic girls and a historian passionately devoted to piecing together Kolno’s history, took me on a walking tour. First we went to the synagogue, which is today a hotel that still has an intact Bimah and Ezrat Nashim, with many Stars of David but no Jews. A group of local women gathered there for a meeting. Behind it was the Schule, the Torah school--now an empty lot. “The Margolis house was at the corner of the market square, the center of town.” Every Thursday from all over the area used to come here for the market. Now, it is a large beautiful square surrounded by two-story buildings, with planted trees and flower beds. “You see where the bank is, great location,” Michal said. “It was an empty lot for many years.” I did not know what to feel, it looked like Afula in the sixties, a small God-forsaken simple town. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine the house through my mother’s stories. The big door that opened to a big yard. The two storage rooms on each side of the door, one for wheat grain, the other for wood. Her merchant father Yaacov, who died of typhus at the age of 35 after a long train ride, selling his wares in distant towns during the winter. I tried to imagine the smell of fresh challah loaves in the bakery my grandma Rashka opened after his death, with her worker Mordechai, who I visited in Afula with my mother many years later. I tried to imagine my mother, the elder daughter who, as an eight-year-old, had to drop out of school to help her mother raise her younger siblings Leah, Tuvia and Eli, as she bravely fought off Russian soldiers who tried to steal bread from the family store. “My mother was too afraid of them, and I had to protect us,” she use to say. I tried to imagine how the whole family lived together on the second floor. I cut some yellow, white, and purple wildflowers. I am sure my mother and her sister knew their names and loved them as children. I laid them on the steps of PKO State Bank. I closed my eyes, touched the building column and said a prayer for her, Leah, Tuvia, Eliyahu, my grandmother Rashka, my grandfather Yaacov, my great-grandfather--the famous healer and Kabbalistic Rabbi Mordechai Zundel Margolis, whose name traveled all the way to America, where I now live--his unnamed wife, my mother’s uncle Arie and his wife Rivkah and all those I never knew. Then Michal suggested we walk down to the Shtetel, the last remaining two old streets that have a few original buildings and still have stone paved roads. We passed by the old church and the theater. “These are the original buildings,” Michal said. We walked to the old Mikvah and stood for a while. And then I started to get a vision of Jews walking just before Shabbat with Kedusha, sacredness, from their houses on the square to the Mikvah. The place became alive again, in my mind, like an old forgotten memory with its smells, beauty, sounds, juxtaposed with the mud, freezing cold and real hardship. As we sat back at his home, Michal was eager to show me his Kolno History website and the article he wrote about Tamar and Aviva’s visit, for which he later got the comment: “Are you working for the Jews?” He showed me documents and pictures and explained the long complicated history of Kolno through the centuries. From a small village, it became an important border town for trading that constantly changed hands between the Prussians, Germans and Russians. He described a big fire that destroyed most of the town and showed how they rebuilt it. At its height, the Jewish population was about 3,500 people, about 75% of the entire town’s population. He showed me an old business directory that lists our bakery. Today, about 10,000 people live in Kolno and there is not one declared Jew. I was so grateful to Hashomer Hatzair Zionist vision for rescuing our family from that place just in time before the war. “Chazak Ve’Ematz!” “We have to go now,” Wlodek hurried me. I wanted to finish my Dobre Kawa, special coffee only Wlodek knows how to make, and finish the plate of strawberry pierogies Michal served, when a loud siren pierced the air. For a moment I thought I was in Tel Aviv and another war had begun. Michal and Wlodek stood up. “It is August 1st at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, when the Warsaw Uprising against the Nazis began.” Michal informed me. I looked through the window. Everything and everyone stopped. I climbed again into the Aqua Florida-smelling camper and we headed back to Warsaw. Wlodek and I were both tired emotionally, and physically. We passed beautiful landscapes of green forests and pastures. We saw storks feeding their young ones in their high nests and teaching them to fly. Life continued. We have a new granddaughter, our second son got married, and our daughter is on her way. My sister, brothers and cousins have children and grandchildren. We are building a new tribe. Life goes on. “Are you Jewish, Wlodek?” I asked him again, as we continued our three hours journey. “I don’t know. I think one of my grandparents was.” As night fell we entered Warsaw. Darius awaited us at a beautiful, chic outdoor cafe on the ground floor of a super modern office building. It was built where the border of the old Jewish Ghetto once stood. As we walked home, we saw bouquets of flowers laid on the sidewalk with candles burning by them. On the wall above hung an iron plaque commemorating the dead. Warsaw has not forgotten. |